Aim: To select foods that I do not particularly enjoy the taste of, but would like to eat consistently, in order to see if simple exposure improves self-reported taste measurements.

Introduction: Scientific studies suggest food exposure to be one of, if not the, most important factor when determining if you like a food or not. Several studies report between 10-15 times being the optimum frequency of food trials before one can truly make a judgement on food fondness.

Method: Over a timescale of 4-6 weeks, 5 carefully (non-randomised) selected foods, based on different levels of a self-reported food rating scale (See table 1). Were decided upon, based on one food from each level (1-5), to see if the level of dislike is influential in liking a food. Fifteen portions of each food will be consumed. No more than 1 portion each day and each food will be consumed on its own as plain as possible.

Table 1. A self-reported rating scale of food and the 5 foods for this experiment

| 0 | Spew | |

| 1 | Cowk | Olives |

| 2 | Boke | Liver |

| 3 | Minging | Aubergine |

| 4 | Yuk | Grapefruit |

| 5 | Neutral | Cottage Cheese |

| 6 | Moorish | |

| 7 | Yum | |

| 8 | Tasty | |

| 9 | Delicious | |

| 10 | Exquisite |

*spew = vomit, cowk = gag reflex, boke = think you may vomit, minging = disgusting, yuk = dislike, neutral = no affiliations/never eaten, moorish = makes you want to eat more.

Olives – Without a doubt, for me, the worst tasting food I was prepared to add to this list. They have a bunch of health benefits such as the ability to reduce heart disease and blood pressure as well as full of antioxidants. They are often linked to reasons for good health in the Mediterranean. The movies make olives look really appealing in cocktails so this helps me want to like them. Also, they are sometimes served as free starters in restaurants I go to. 1 portion = 10 olives

Liver – We as a nation are eating fewer and fewer nutrient dense organ meats. I want to overcome my Western fear of “gross” organ meats and see them for their health properties and rich sources of vitamins A, D, E, K, B12 and folic acid, and minerals such as copper and iron. Beef (ox) liver is reported to be the least bitter so this will be used. Will cook on George Foreman with no oil to reduce interference from flavours. 1 portion = 100g

Aubergine – a vegetable stuck in the common cycle of I don’t like – I don’t buy = very few exposures. It’s been so long, I can’t even picture what they taste like. Research on aubergines has focused on nasunin. It is a potent antioxidant, protecting the fatty acids essential for healthy brain function as well as assisting excess nutrients out of the body, where build up may not be beneficial. Can be eaten raw but will cook on George Foreman with no oil. 1 portion = 1/3 an aubergine

Grapefruit – To me, tastes like an orange after I have brushed my teeth. They have a bitter twang that simply does not agree with me and have often avoided. This breakfast fruit can help with blood pressure and heart health. The powerful nutrient combination of fibre, potassium, lycopene, vitamin C and choline in grapefruit all help to maintain a healthy heart. One study found that a diet supplemented with fresh red grapefruit positively influences blood lipid levels, especially triglycerides (good cholesterol). 1 portion = whole grapefruit.

Cottage cheese – Some might class this as a copout selection. Needed a neutral food that didn’t have any affiliations with, but I have never really eaten cottage cheese despite it being high in protein, in particular, casein, which is slow digesting and can be beneficial before bed to stop any muscle breakdown during the night fast. 1 portion = 100g

Each food will be consumed in isolation of other foods as to avoid cross-contamination. No more than 1-2 foods from the trial will be consumed in a 24-hour period. Each food will be consumed on a relatively empty stomach (where possible) to limit gastrointestinal interference, which has been reported to be a major factor in food avoidance. Olives, aubergines, and liver will generally be consumed as a starter before lunch or evening meal, cottage cheese typically before lunch or late at night and grapefruit before breakfast. Results will be recorded with-in 5 minutes after completion of the final bite using the table below. Each food will be rated individually along with a daily log of anything noteworthy. A full analysis will be completed once all 15 x 5 portions have been completed.

Once completed, a follow-up study may be initiated, using other methods to improve food preferences.

Hypothesis: Can consistent food exposure to neutral and disliked foods improve the self-reported taste? No predictions are being made to avoid any potential bias.

Results:

Table 2. Month 1. Each food rated 0-10, across 7 separated trials

| BL | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Olives | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| *Liver | 2 | 2 | 2 | x | ||||

| Aubergine | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Grapefruit | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| Cottage Cheese | 5 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

Table 3. Month 2. Each food rated 0-10, across 8 separated trials

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

| Olives | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| *Liver | ||||||||

| Aubergine | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Grapefruit | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Cottage Cheese | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

*The liver trial was terminated due to a fellow dweller not being able to handle the smell omitted during cooking procedures.

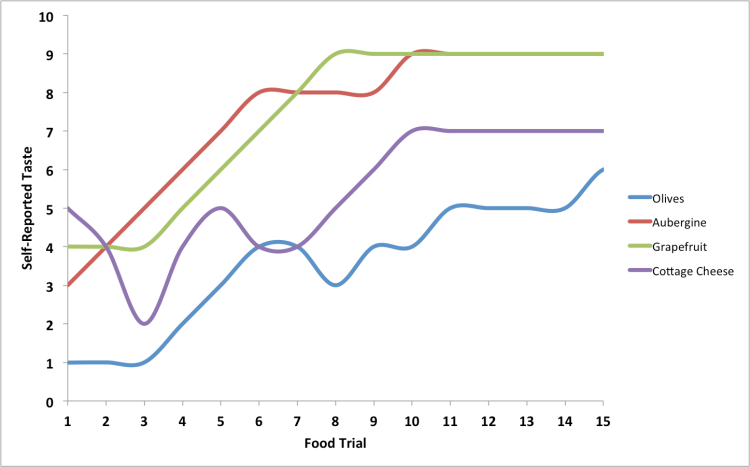

Self-Reported Food Trial Graph

Graph 1. Self-reported food trials observed across 15 trials.

All trials observed a gradual linear increase in self-reported taste, with cottage cheese being the possible exception displaying a undulating result. The average increase in self-reported food taste was 4.5 ± 1.5 (range 2 – 5). Foods which, started of with lower rating food scores, generally observed the largest increase in reported taste. Several foods (cottage cheese, grapefruit and Aubergine) score plateaued after 9 trials while the olive trial seen continual increase.

Conclusion

As predicted, and in accordance with other research, with perseverance and a well planned strategy, even the most disliked of foods can become palatable or even delicious. The results are clear for all to see.

Food abundance has made us fussy and being a fussy eater can create a vicious cycle, by passing on habitual eating prejudices as well as lack of food exposure in early foetal development/childhood. The affordability of food and modern parenting methods, have typically moved on from ‘old fashioned’ methods, where you were provided with a meal and a take it or leave it option, the latter resulting in the same meal returned for the proceeding meal.

We are mistaken to believe that we eat the food we like, where it is quite the opposite. You will like the food you eat.

References

ADDESSI, E. et al., 2005. Specific social influences on the acceptance of novel foods in 2-5-year-old children. Appetite, 45(3), pp. 264-271

CARRUTH, B.R. et al., 2004. Prevalence of picky eaters among infants and toddlers and their caregivers? decisions about offering a new food. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 104, Supplement 1, pp. 57-64

COOKE, L., WARDLE, J. and GIBSON, E.L., 2003. Relationship between parental report of food neophobia and everyday food consumption in 2?6-year-old children. Appetite, 41(2), pp. 205-206

COULTHARD, H. and BLISSETT, J., 2009. Fruit and vegetable consumption in children and their mothers. Moderating effects of child sensory sensitivity. Appetite, 52(2), pp. 410-415

FALCIGLIA, G.A. et al., 2000. Food Neophobia in Childhood Affects Dietary Variety. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 100(12), pp. 1474-1481

FARROW, C.V. and COULTHARD, H., 2012. Relationships between sensory sensitivity, anxiety and selective eating in children. Appetite, 58(3), pp. 842-84

GALLOWAY, A.T. et al., 2005. Parental pressure, dietary patterns, and weight status among girls who are ?picky eaters? Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 105(4), pp. 541-548

GIBSON, E.L., WARDLE, J. and WATTS, C.J., 1998. Fruit and Vegetable Consumption, Nutritional Knowledge and Beliefs in Mothers and Children. Appetite, 31(2), pp. 205-228

HENDY, H.M. and RAUDENBUSH, B., 2000. Effectiveness of teacher modeling to encourage food acceptance in preschool children. Appetite, 34(1), pp. 61-76

HURSTI, U.K. and SJ�D�N, P., 1997. Food and General Neophobia and their Relationship with Self-Reported Food Choice: Familial Resemblance in Swedish Families with Children of Ages 7?17 Years. Appetite, 29(1), pp. 89-103

JACOBI, C. et al., 2003. Behavioral Validation, Precursors, and Concomitants of Picky Eating in Childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(1), pp. 76-84

KNAAPILA, A. et al., 2007. Food neophobia shows heritable variation in humans. Physiology & Behavior, 91(5), pp. 573-578

MARCONTELL, D.K., LASTER, A.E. and JOHNSON, J., 2003. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of food neophobia in adults. Journal of anxiety disorders, 17(2), pp. 243-251

PELCHAT, M.L. and PLINER, P., 1995. ?Try it. You’ll like it?. Effects of information on willingness to try novel foods. Appetite, 24(2), pp. 153-165

PLINER, P., 1994. Development of Measures of Food Neophobia in Children. Appetite, 23(2), pp. 147-163

PLINER, P. and HOBDEN, K., 1992. Development of a scale to measure the trait of food neophobia in humans. Appetite, 19(2), pp. 105-120

PLINER, P. and LOEWEN, E.R., 1997. Temperament and Food Neophobia in Children and their Mothers. Appetite, 28(3), pp. 239-254

PLINER, P., PELCHAT, M. and GRABSKI, M., 1993. Reduction of Neophobia in Humans by Exposure to Novel Foods. Appetite, 20(2), pp. 111-123

RAUDENBUSH, B. and FRANK, R.A., 1999. Assessing Food Neophobia: The Role of Stimulus Familiarity. Appetite, 32(2), pp. 261-271

RITCHEY, P.N. et al., 2003. Validation and cross-national comparison of the food neophobia scale (FNS) using confirmatory factor analysis. Appetite, 40(2), pp. 163-173

RUSSELL, C.G. and WORSLEY, A., 2008. A Population-based Study of Preschoolers? Food Neophobia and Its Associations with Food Preferences. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 40(1), pp. 11-19

SKINNER, J.D. et al., 2002. Children’s Food Preferences: A Longitudinal Analysis. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 102(11), pp. 1638-1647

SMITH, A.M. et al., 2005. Food choices of tactile defensive children. Nutrition, 21(1), pp. 14-19

TUORILA, H. et al., 2001. Food neophobia among the Finns and related responses to familiar and unfamiliar foods. Food Quality and Preference, 12(1), pp. 29-37

WARDLE, J., CARNELL, S. and COOKE, L., 2005. Parental control over feeding and children?s fruit and vegetable intake: How are they related? Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 105(2), pp. 227-232